What do presidential elections mean for your portfolio?

The 2020 US presidential election is here and Wall Street is not shying away from commentary.

For weeks, investors have been bombarded with predictions, surveys, market reports, and more – all while we face other unprecedented factors like the ongoing pandemic. Fueled by high levels of voter engagement and a polarized political climate, it’s reasonable to contemplate how the markets will react regardless of your politics.

Even those of us focused on the long-term may wonder what we should be doing. But before we even consider outcomes, there’s another question to ask first:

Does the presidential election cycle impact your portfolio?

While past performance doesn’t indicate future performance, the stock market is cyclical. That means we’re able to identify historical patterns in past election years, though we can’t say the pattern will happen again in 2020.

Here’s how past presidential elections impacted the US stock market and what this could mean for your portfolio in the coming weeks:

The Presidential Cycle Indicator: how past presidential elections have impacted the US stock market

The idea that the presidential election cycle is important to investors isn’t new.

Yale Hirsch, founder of the Stock Trader’s Almanac in 1967, developed the first version of The Presidential Cycle Indicator — a theory that examined stock market performance and presidential election cycles. The decades-old theory is still accepted today.

At its core, The Presidential Cycle Indicator outlines decades of historical data to show that the first two years of a presidential term coincided with weaker stock market performance than the last two years.

Hirsch hypothesized that a motivated president shifts from campaign mode to action mode during the first two years of a term. They begin to work on their agenda and enact new policies.

Since it takes time for new policies to be implemented, the stock market performance during the second year of a presidency should be stronger than the first year (which is typically the weakest during the four-year term).

In the third and fourth years, Hirsch suggests that the focus shifts back to the next election. This may motivate a president’s efforts to strengthen the economy. For this reason, the third and fourth years of a term are often stronger than the previous two. Per Hirsch:

- The first year post-election is the weakest.

- The second year is also the year of midterm elections. This year proves better than the first but is typically the second-weakest.

- In the third year, the economy starts to ramp up in the year before the next presidential election. This is typically the strongest year of a presidency.

- The fourth and final year is the second-strongest year of a four-year term.

Attempts to shore up voter support for the incumbent party may appear in the form of different types of policy changes. These may include tax cuts, an increased effort to create jobs, or some combination of the two. All potential economic factors.

The past doesn’t always repeat itself

While there are several studies that show data trends aligned with Hirsch’s theory (or other election/market predictions), there are many that disprove it.

For example, Kiplinger studied the Dow Jones Industrial Average’s performance since 1933. Kiplinger found that in the first and second years of a president’s term, the Dow saw average gains between 2.5% and 4.2%, respectively.

During this period, they also found that the Dow gained an average of 10.4% in the year before a presidential election and an average of almost 6% in the election year itself.

So Hirsch’s indicator must work, right?

Not necessarily.

The indicator’s recent predictions have not been accurate. One notable exception happened in 2008, when the Dow sank nearly 34%.

And Barack Obama’s presidency included several exceptions. During his two terms, the S&P 500 fluctuated:

- 2009: +23.4%

- 2010: +12.7%

- 2011: +0%

- 2012: +13.4%

- 2013: +29.6%

- 2014: +11.3%

- 2015: -0.7%

- 2016: +9.5%

These numbers contradict Hirsch’s theory that the second year of a four-year term is the weakest. In fact, at +0%, the third year of Obama’s first four-year term was the weakest — as was the third year of his second four-year term at –0.7%.

Still, we’re seeing predictions fly left and right.

Remember that if people could accurately predict the market, they’d already be Warren Buffet-level wealthy. If you need daily reminders, we tweet these out with frequency:

The Party Changeover Indicator: how past party changeovers have impacted the US stock market

Setting the presidential cycle indicator aside for a moment, let’s look at an interesting anomaly that appears leading up to elections: The Party Changeover Indicator.

This one doesn’t necessarily have a name, but says that if the stock market is up in the three months before an election, the incumbent typically maintains their position. However, stock market losses in the three months prior to the election often pave the way for a new party.

According to Kiplinger editor Anne Kates Smith:

“In the 23 president elections since 1928, 14 were preceded by gains in the three months prior. In 12 of those 14 instances, the incumbent (or the incumbent party) won the White House. In eight of the nine elections preceded by three months of stock market losses, incumbents were sent packing. (Exceptions to this correlation occurred in 1956, 1968 and 1980.)”

Whether Democrats or Republicans win doesn’t seem to make much of a difference when it comes to stock returns.

The conventional notion is that the Republican party is more likely to make efforts to stimulate economic activity by helping corporations generate earnings. Hypothetically, that’s good news for the stock market: earnings are what’s needed to juice stock prices over the long term.

But the reality is that the stock market has performed better with Democrats in the White House.

According to results of Kiplinger’s deep dive, the average return for the stock market since 1900 is 3.5% when Republicans are in control and 6.7% when Democrats are in charge.

But during the 2020 election cycle and pandemic? For what it’s worth, the S&P 500 was up in the three months before the 2020 election. But jury’s out as of the writing of this article.

Expect volatility, but know it’s not permanent

Financial markets may see increased volatility around elections because investors don’t like uncertainty — that doesn’t mean there’s trouble ahead.

Let’s think back to 2016.

On election night, it was unclear how financial markets would react to Trump’s victory. Shortly before November 8, 2016 at 11:00 PM on the East Coast, major networks called Ohio and Florida in favor of then-candidate Donald Trump.

Futures – financial instruments that trade day and night – seemed to indicate that the market might lose as much as 1,000 points the next day.

The knee-jerk reaction was short-lived.

Stock markets finished the day with solid gains on November 9, 2016. Sentiment shifted from fear and panic to a more rational assessment as investors realized something important: no political leader controls the stock market directly.

A president may set the tone for trade, enact other policies, and put forth a broad economic agenda, but these actions take time to translate into changes in corporate earnings and share prices. Although the president has the power to make political appointments (including the Chair of the Federal Reserve, which sets interest rates), no one has the power to flip a switch and make the stock market move.

Like other moments of market volatility, if you’re in it for the long-term it probably won’t matter as much anyway.

And if you’re only day or swing trading, why?

Like every election season, your mindset matters

With history covered, let’s come back to our question: does the presidential election cycle impact your portfolio?

The answer is yes, in the sense that any major event could affect the market. But the presidential office is just one piece of the country’s economic puzzle.

Realistically, no market timing tool is reliable enough to warrant major changes to a long-term investment strategy. Even policies that are expected to have a certain impact on the market can end up doing the exact opposite.

So, while it’s wise to keep one eye on broader economic indicators, stay focused. Your mindset matters during heavy news cycles more than ever before.

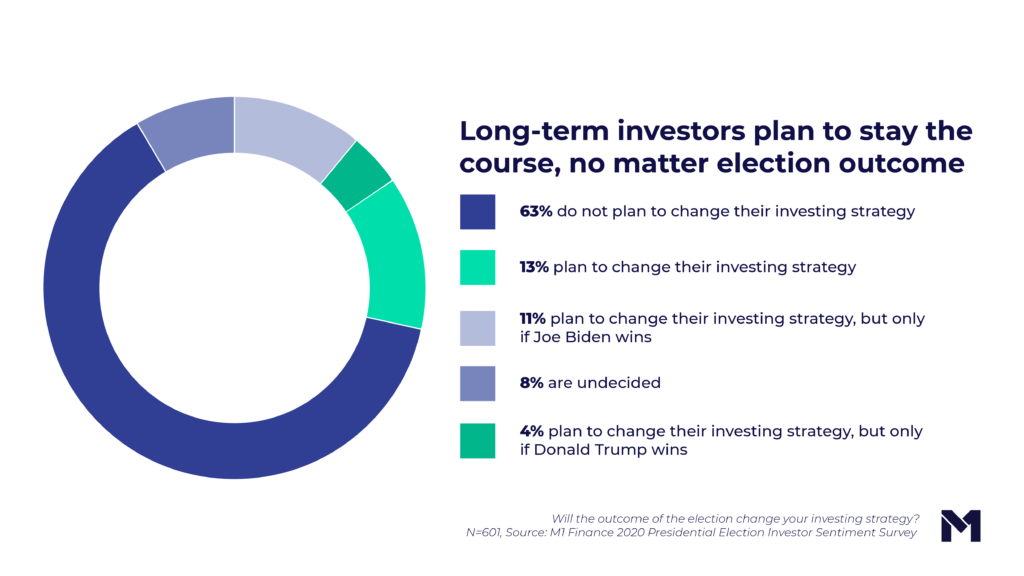

There will be noise, there will be bumps, but you’re in it for the long haul. If it helps, 63% of investors are right there with you:

- Categories

- Invest