What is cost basis?

Cost basis is the original price you paid for an investment you own inclusive of fees and commissions. When you sell a security, you use the cost basis to calculate your profit or loss. This, in turn, is used for tax purposes.

If you’ve ever sold an asset, you’ve probably had to report the cost basis when filing your taxes. The IRS requires taxpayers to calculate their own cost basis, although for securities like stocks and bonds your brokerage may calculate cost basis for you as well.

There are three main methods to determine your cost basis.

- First In, First Out (FIFO)

- Average cost

- Specific shares

The tax implications of cost basis

When you sell an asset and realize a profit or loss, it may be considered a taxable event. To find the difference, you must calculate the tax basis. This will reveal the tax consequences of the sale.

Cost basis is important because investors often buy and sell assets at different times. So, if you bought 10 shares of BLBRY in one year and 10 shares of BLBRY in another year, if you later sell 15 of the 20 total shares, your cost basis could be different depending on how much of each set of shares you sell.

Examples of cost basis

Cost basis is used to calculate a variety of investment actions. We’ll look at how cost basis is used when investing in securities, although any asset that is bought at one price and sold at another can be said to have a basis.

Buying and selling securities

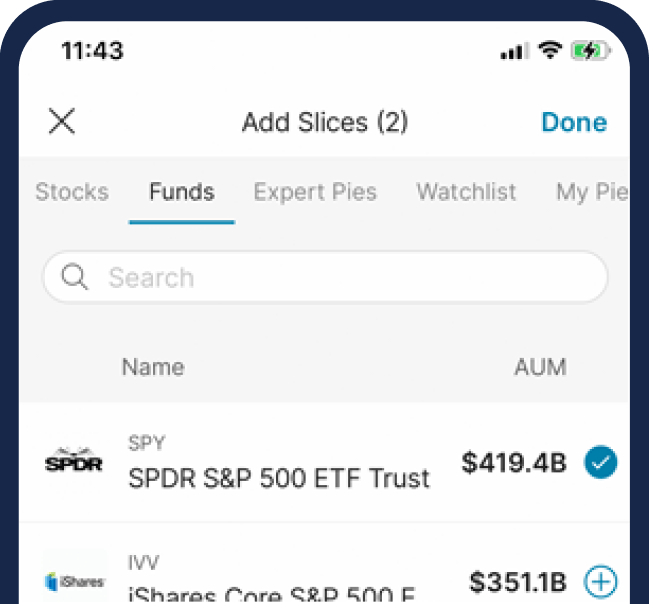

For securities like stocks, bonds, or publicly traded funds like ETFs and mutual funds, the cost basis is typically equal to the price you paid for each share, along with any commission and trading fees to your broker.

Dividends

If you reinvest a dividend, the cost basis for those shares is the price of the new shares or fraction of shares paid for by the dividend.

Open your brokerage account or IRA with M1 and start your wealth-building journey today. Our automated tools put the controls in your hands.

Stock splits

In the event of a stock split, your original cost basis remains unaffected. However, your per-share cost basis changes based on the stock split. So, if you own 10 shares of RSBY that you bought for $10 per share, your cost basis would be $100. Now if RSBY declares a 2-for-1 stock split, you now own 20 shares. However, your cost basis still remains at $100. The only change is your per-share cost basis which decreases to $5.

Stock mergers and acquisitions

If a company you own shares of merges with another, your total cost basis generally remains unaffected. However, if you receive new shares as part of the merger, these shares could have their own cost basis.

How to calculate cost basis

For calculating the cost basis of securities like stocks and bonds, there are three main methods:

First In, First Out (FIFO)

FIFO is one of the most commonly used methods for calculating the cost basis of your equities. This method assumes that the first shares you purchased are the first ones you sell.

To calculate using FIFO:

- Order your transactions: Starting with the earliest buys, list all of your investments in chronological order.

- Calculate the cost basis: When you sell, you’ll start with your oldest shares, so your cost basis will be calculated according to the value of those shares. Multiply the number of older shares sold by the cost per share from the same purchase.

- Repeat for each sale: Continue this process for each subsequent sale, working your way up from the oldest purchases to the most recent ones.

Note that your brokerage will often calculate and display the cost basis for you. However, it’s important to know how it works because it will help you understand when or if you want to sell.

Example:

You bought five shares of PMKN on October 1st for $250. Each share cost $50. On October 15th, PMKN was trading at $70 per share and you decided to purchase five more shares for $350. Using the FIFO method, if you were to sell two shares, your cost basis would be $100 since $50 per share is the price you paid first.

Now, you decide to sell seven shares of PMKN. Using the FIFO method, your cost basis for the first three remaining shares would be $50 per share, or the cost of the first shares you bought. Your cost basis for the other four shares would be $70 per share, or the cost of the second round of shares purchased.

Average cost

The average cost method is when you calculate your cost basis by averaging the cost of all shares you own. This method can be used for mutual funds.

To calculate average cost:

- Add up the total amount you’ve spent.

- Determine the total number of shares you own.

- Divide the total investment by the total number of shares. This will give you the average cost per share.

Average cost is a simplified way to display cost basis without having to list out every share purchased on every date throughout history.

Example:

You bought five shares of CBTR fund for $50 each and then 5 more shares for $70 each, the cost basis would be the total cost of $600 divided by the total numbers of shares of 10 equaling $60 per share.

Specific shares

The specific shares method lets you choose which shares you want to use for this cost basis calculation.

The specific shares method can be used to save on capital gains tax. You can sell shares that have the lowest margin so that you end up owing the lowest amount of tax even when the sale price is the same.

The specific shares method can also be used to take advantage of strategies like tax-loss harvesting in certain portfolio situations.

To calculate specific shares:

- Identify the specific shares: When you sell some of your portfolio, you’ll need to specify which shares you’re selling. Make sure to keep track of your purchases with dates and prices if your brokerage doesn’t let you choose by lot.

- Calculate the cost basis: For each sale, you’ll use the actual cost of the specific shares you’ve selected to calculate your cost basis.

- Document your choices: It is important to keep track of your selections to provide to the IRS if needed.

Example:

You bought 100 shares of BLBY a year ago for $2 a share at $200 total.

You then buy another 100 shares for $12 a share at $1,200 total sometime later.

A few months later, the shares have increased to $20 so you decide to sell 100 of them.

If you decide to sell the shares from the first purchase, your cost basis for the 100 shares sold would be $200. The proceeds from selling 100 shares at $20 per share would amount to $2,000, resulting in a capital gain of $1,800.

If you decide to sell the shares from the second purchase, the cost basis for the 100 shares sold would be $1,200. The proceeds from selling these shares at $20 per share would still be $2,000, but the capital gain, in this case, would be $800.

By specifically identifying the shares you want to sell, you can determine which tax strategy works best for you.

The M1 line

M1 Finance uses built-in tax efficiency to help investors to reduce the amount that they might owe on taxes automatically.

However, you may still need to file a few additional forms with the rest of your return when you sell. Always consult a tax professional when tax planning.

Understanding cost basis is fundamental to effectively reporting your taxes and optimizing your financial strategy.

DISCLOSURES:

M1 and its affiliates do not provide tax, legal, or accounting advice. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, tax, legal or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax, legal, and accounting advisors before engaging in any transaction.

20231110-3206130-10208788